There’s an old adage: the best place to start is at the beginning. Right, but if you’re telling a story, you might feel that spelling that out doesn’t exactly make for the best of openers. Given the absence of any preceding words, it’s a fair assumption the reader knows they’re at the start. With a remit to find three golden opening words, one might regret wasting the opportunity with In the beginning. Arguably, Melville’s Call me Ishmael makes a finer fist of it.

However, if, like me, you believe the Bible’s an encounter with Ultimate Truth through the power of story then there can be no wasted words. A deeper reality is always waiting to be discovered.

The Once upon a time that often opens fables has, interestingly, a certain timeless quality to it and there’s something similar at work here. A fable doesn’t have to be literally true to be fundamentally true. The classroom question, ‘What’s the moral of the story?’ hardly requires explanation. Is it crucial that there was ever an actual boy who cried wolf? What about not messing around the people your life might depend on one day?

So, in one sense, we’re already in the realm of the fabulous because, well, who’s honestly around to tell this tale from the start? But, ironically, that’s the telling point which wreathes the apparently pedestrian opener with golden primordial light. Quite literally, from the off, we’re taking God’s word for what follows. It’s told in the third person but, of course, only He can be the true narrator. So, this isn’t merely the opening of any story but of every story. It’s the beginning of story itself.

Now the beginning isn’t obvious at all and calling it the beginning is the opposite of self-explanatory. It feels more like a cipher to a murder mystery designed to hook the reader to the end of the tale. With these three simple words we find ourselves instantly drawn into an unsettling intimacy. The very opposite of a bad story start! We’re getting to witness the stuff of CERN fantasy first-hand: nothing short of the origins of the universe. But it’s truly too mind-blowing to comprehend which is why it’s told as a story. After all, when does the beginning actually begin? How does one measure the transit from timelessness to time? So, we’re getting to see what cannot rightly be seen with the human eye – like suddenly beholding the total shape of love.

It’s an astonishing privilege of imagination to stand at the demarcation between non-existence and existence, nothing and everything, darkness and light, chaos and order, emptiness and fullness, between silent hidden impulse and astounding vocal power. Brilliantly captured in those first three words, we hear the human voice interwoven with Divine Word. Whoever penned them well knew they’re fundamentally unlike Once upon a time. It absolutely matters that this is more than a fable or a simple morality tale. From the outset, the figurative is at service to the revelation of reality, and God here is most certainly real.

Now, whether or not you’re convinced by its vision is a rather different question. But, given its subject matter, I think it’s an easy case to make that it’s one of the most deceptively brilliant starts to a story ever written. And to anyone interested in story as a journey of discovery into a deeper sense of reality, this, at the very least, ought to be enough reason to read on.

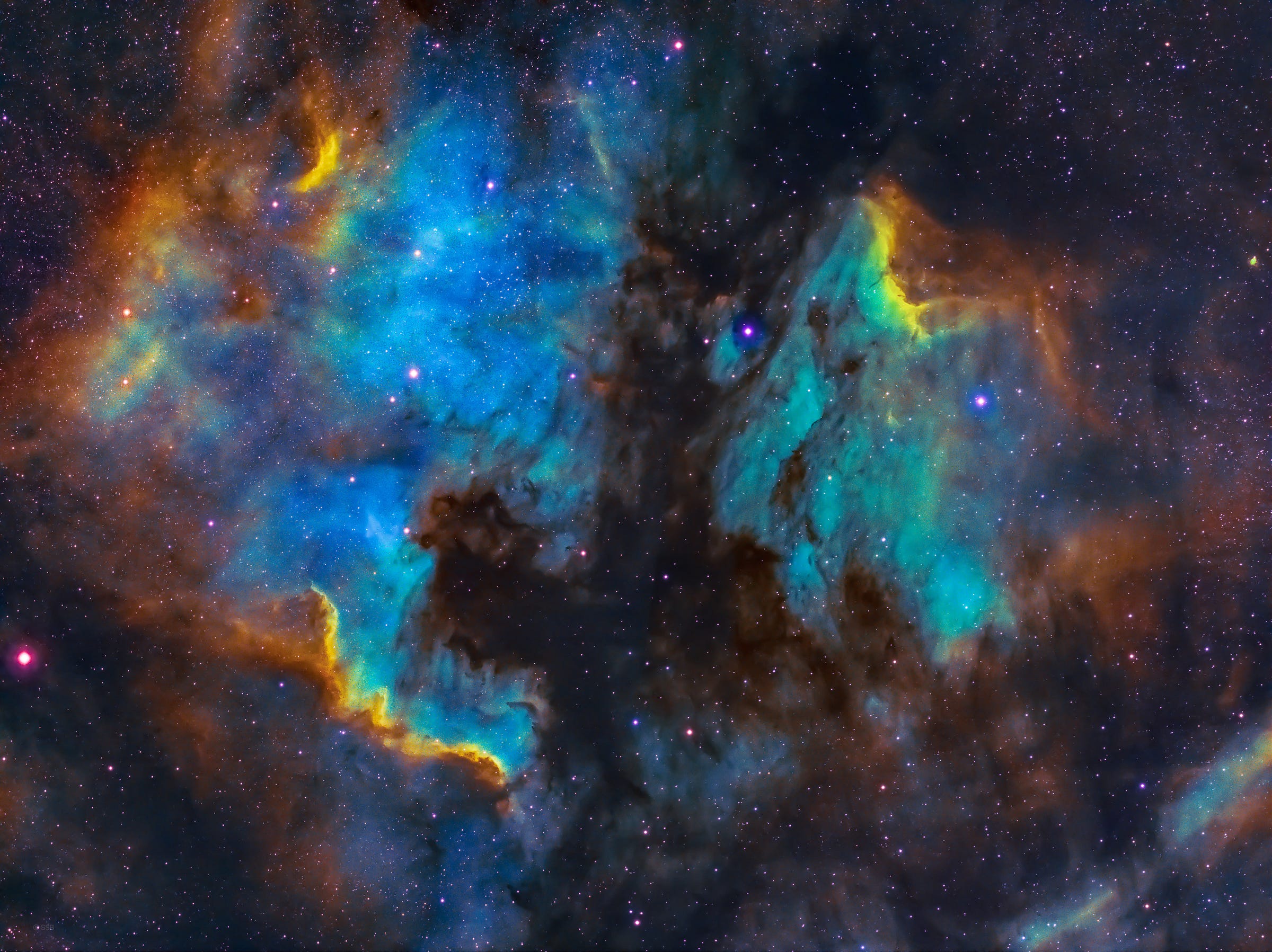

Header photo: Aldebaran S, Unsplash